Michigan gardens can become buzzing havens for bees, butterflies, and other helpful pollinators with the right plant choices. Creating a pollinator-friendly space means selecting native and adapted plants that thrive in Michigan’s unique climate while providing nectar and pollen throughout the growing season. Your garden can play a vital role in supporting these essential creatures while adding beautiful colors and textures to your outdoor space.

1. Purple Coneflower (Echinacea purpurea)

Nothing says “welcome” to pollinators quite like the cheerful purple coneflower with its bright pink-purple petals and prominent orange center. Bees absolutely love landing on these sturdy flower heads, which act like perfect landing pads for their nectar-gathering missions. Butterflies also find these blooms irresistible, especially during late summer when other flowers start fading.

Growing purple coneflowers in your Michigan garden couldn’t be easier since they’re incredibly tough and drought-tolerant once established. These perennials come back year after year, getting bigger and better with each season. They bloom from July through September, providing consistent food sources when pollinators need them most.

The seed heads that form after flowering aren’t just attractive winter decorations – they’re also valuable food sources for birds like goldfinches and chickadees. Many gardeners leave the spent flowers standing through winter specifically to feed their feathered friends. Come spring, you can cut back the old stems to make room for fresh growth.

Purple coneflowers work beautifully in both formal garden beds and wildflower meadows. They pair wonderfully with black-eyed Susans, bee balm, and native grasses. Plant them in full sun to partial shade, and don’t worry too much about soil conditions – they adapt to most garden situations as long as drainage is decent.

2. Wild Bergamot (Monarda fistulosa)

Wild bergamot creates quite the spectacle when dozens of bees compete for space on its fuzzy, lavender-pink flower clusters. Native Americans traditionally used this aromatic plant for medicinal teas, which explains why it’s sometimes called “bee balm” – though true bee balm is actually its red-flowered cousin. The minty fragrance fills the air whenever you brush against the leaves, creating a sensory garden experience.

Michigan’s native wild bergamot thrives in prairie-like conditions and spreads naturally through underground roots, creating impressive colonies over time. This spreading habit makes it perfect for naturalizing large areas or filling in gaps between other perennials. The tubular flowers are specially designed for long-tongued bees and butterflies, though shorter-tongued insects also find ways to access the nectar.

Hummingbirds occasionally visit wild bergamot flowers, adding another layer of wildlife interest to your garden. The plant blooms from June through August, coinciding perfectly with peak pollinator activity in Michigan. After flowering, the interesting seed heads provide architectural interest and bird food through fall and winter.

Plant wild bergamot in full sun to light shade in average garden soil – it actually prefers lean conditions over rich, fertilized ground. Too much fertility can cause the plants to flop over or become too aggressive. Regular division every few years helps maintain healthy clumps and gives you extra plants to share with neighbors or expand your pollinator garden.

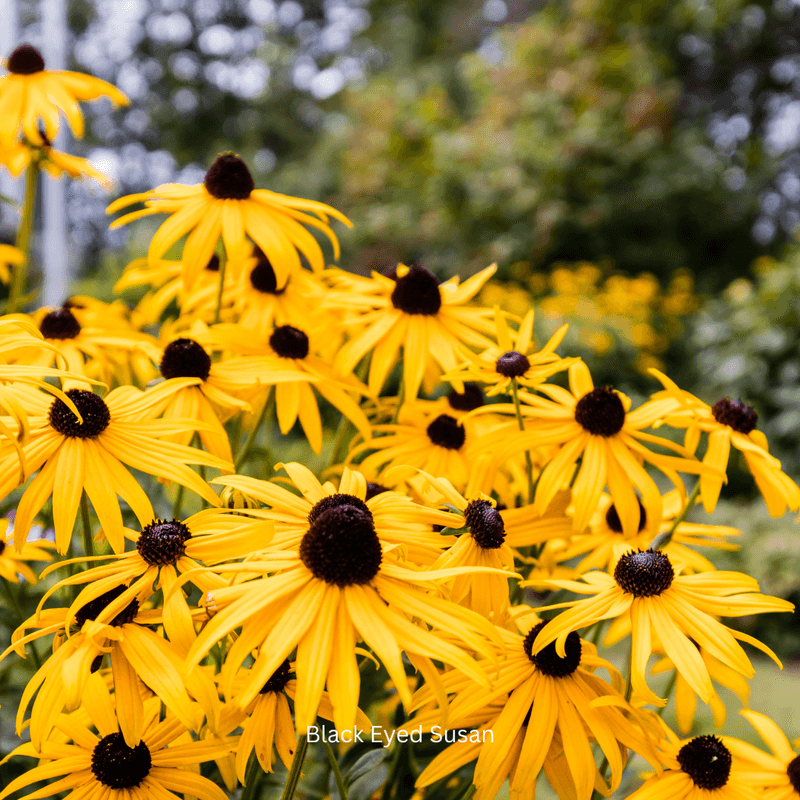

3. Black-Eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta)

Cheerful black-eyed Susans light up Michigan gardens like little suns, their golden petals radiating around dark chocolate centers that practically magnetize bees and butterflies. Watch any patch of these flowers on a sunny day and you’ll see constant pollinator traffic – bees methodically working from flower to flower while butterflies dance overhead. The contrast between bright petals and dark centers helps pollinators locate nectar sources from impressive distances.

These hardy wildflowers originally called Michigan’s prairies home, making them perfectly adapted to our climate extremes and soil conditions. They handle drought like champions once established, yet also tolerate occasional flooding better than many garden plants. Black-eyed Susans typically live for two to three years but self-seed so readily that established patches maintain themselves indefinitely.

The long blooming period from June through October makes black-eyed Susans incredibly valuable in pollinator gardens. Early season flowers feed spring bees emerging from winter dormancy, while late blooms provide crucial fuel for butterflies preparing for migration or winter survival. Goldfinches particularly love the seeds, often perching directly on flower heads to feast.

Mass plantings create the most dramatic visual impact and provide concentrated pollinator resources. Mix black-eyed Susans with purple coneflowers, wild bergamot, and native grasses for authentic prairie-style combinations. They thrive in full sun and average to poor soils, actually performing better without fertilization or rich compost amendments that can encourage weak, floppy growth.

4. New England Aster (Symphyotrichum novae-angliae)

Late summer in Michigan wouldn’t be complete without the spectacular purple fireworks display of New England asters blooming just when many other flowers are calling it quits. Monarch butterflies staging for their incredible migration south depend heavily on these nectar-rich blooms to fuel their journey. Each flower head contains dozens of tiny individual flowers, creating abundant feeding opportunities in compact spaces.

Timing makes New England asters absolutely critical in pollinator gardens since they bloom from August through October when food sources become scarce. Native bees preparing for winter hibernation need this late-season nutrition to survive until spring. The flowers also support migrating butterflies beyond just monarchs – painted ladies, red admirals, and various skippers all depend on fall asters.

These robust perennials can reach four to six feet tall, creating impressive background displays in garden borders. The plants naturally form colonies through underground spreading, though they’re not aggressively invasive like some asters. Pinching the growing tips in early summer encourages bushier growth and more flower production, while also preventing the tall stems from flopping over.

New England asters prefer full sun and moist soils but adapt to various conditions once established. They pair beautifully with goldenrod, creating classic fall color combinations that support diverse pollinator communities. Don’t worry if the lower leaves turn brown and drop off during summer – this is normal behavior that doesn’t affect flowering or plant health.

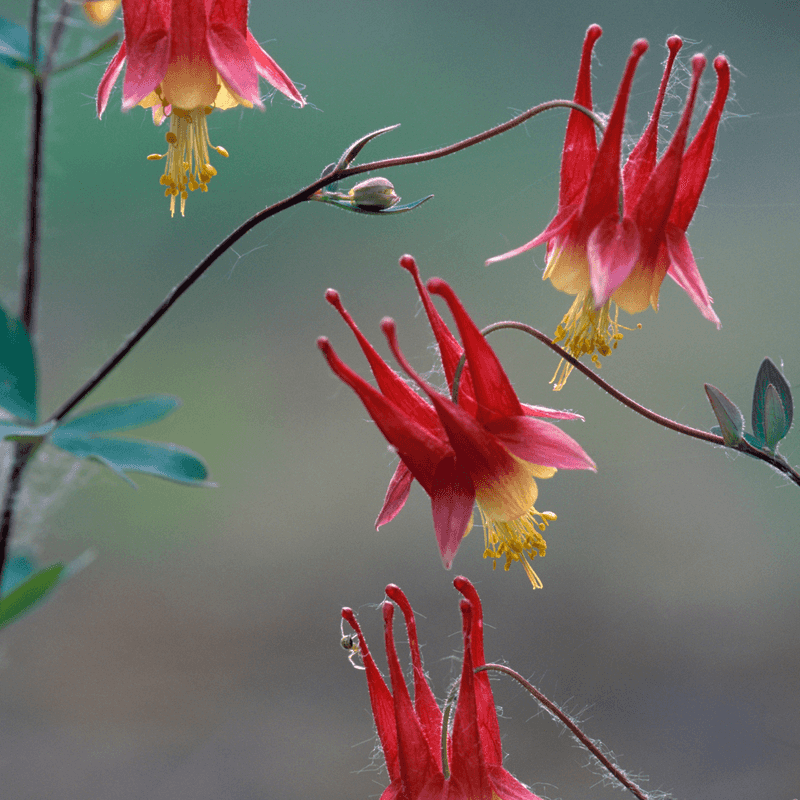

5. Wild Columbine (Aquilegia canadensis)

Delicate wild columbines dance in spring breezes like tiny red and yellow lanterns, their unique spurred flowers perfectly designed for long-tongued pollinators. Hummingbirds are the primary pollinators, hovering expertly to reach nectar hidden deep within the flower spurs. However, bumblebees sometimes “cheat” by biting holes in the spurs to access nectar without providing pollination services – nature’s version of breaking and entering!

Michigan’s native columbine thrives in partially shaded woodland gardens where many other flowers struggle to bloom. The intricate foliage resembles delicate lace, providing attractive groundcover even when plants aren’t flowering. Spring emergence happens early, with flowers appearing from April through June when few other nectar sources are available for newly active pollinators.

Wild columbines self-seed readily in favorable conditions, creating charming naturalized colonies over time. The seeds have interesting adaptations – they’re actually dispersed by ants who carry them away to eat attached nutrient packets, inadvertently planting the seeds in new locations. This ant-dispersal system helps columbines spread gradually through woodland areas.

Plant wild columbines in partial to full shade with well-draining soil that doesn’t dry out completely. They work beautifully in rock gardens, woodland borders, or naturalized areas under trees. The plants typically live three to four years but maintain populations through self-seeding. Leaf miners sometimes create winding trails through the foliage, but this cosmetic damage doesn’t harm plant health or flowering.

6. Swamp Milkweed (Asclepias incarnata)

Swamp milkweed transforms ordinary garden spaces into monarch butterfly nurseries, serving as both adult nectar source and essential caterpillar food plant. Unlike its aggressive common milkweed cousin, swamp milkweed behaves politely in garden settings while providing equal value to monarch populations. The fragrant pink flower clusters attract dozens of butterfly species, creating living bouquets that change throughout the day as different visitors arrive and depart.

Despite its name, swamp milkweed adapts beautifully to regular garden conditions and doesn’t require constantly wet soil. Michigan gardeners find it much easier to manage than common milkweed, which can spread aggressively through underground roots. Swamp milkweed forms neat clumps that expand slowly and predictably, making it perfect for formal perennial borders as well as naturalized areas.

The complex flowers produce abundant nectar that attracts not just butterflies but also bees, beetles, and other beneficial insects. Each flower cluster contains dozens of individual flowers that open sequentially, extending the blooming period from June through August. The resulting seed pods split open in fall, releasing silky-haired seeds that float away on autumn breezes.

Plant swamp milkweed in full sun to light shade in average garden soil with decent drainage. The plants reach three to four feet tall and work well in middle to back border positions. Cutting back spent flower clusters encourages additional blooming, though leave some pods to mature if you want to collect seeds or support natural reseeding. The milky sap can cause skin irritation in sensitive individuals, so wear gloves when handling.

7. Anise Hyssop (Agastache foeniculum)

Anise hyssop creates vertical exclamation points in pollinator gardens with its purple-blue flower spikes that seem to hum with constant bee activity. The licorice-scented foliage releases fragrance with every touch, creating aromatic pathways through garden spaces. Native Americans and early settlers used the leaves for seasoning and medicinal teas, while modern gardeners appreciate how the flowers provide nectar from midsummer through fall.

Bees show remarkable loyalty to anise hyssop, often working the same plants repeatedly throughout the day rather than wandering to other flower types. This behavior, called “flower constancy,” makes anise hyssop incredibly efficient at supporting bee populations. The tubular flowers are perfectly sized for various bee species, from tiny sweat bees to large carpenter bees.

Michigan’s variable weather doesn’t faze anise hyssop, which handles both drought and occasional flooding with equal resilience. The plants self-seed reliably, creating sustainable populations that maintain themselves with minimal intervention. However, they’re not weedy or aggressive – unwanted seedlings pull up easily when young.

Anise hyssop works beautifully in herb gardens, perennial borders, or prairie-style plantings. The flower spikes make excellent cut flowers, lasting well in bouquets while continuing to attract butterflies indoors. Plant in full sun to light shade in well-draining soil. Pinching early flowers encourages bushier growth, while allowing later blooms to set seed provides winter bird food and ensures next year’s plants.

8. Wild Lupine (Lupinus perennis)

Wild lupine stands like blue candles in Michigan’s sandy soils, its distinctive flower spikes supporting not just general pollinators but also serving as the only host plant for endangered Karner blue butterflies. Each flower spike contains dozens of pea-like flowers that open from bottom to top over several weeks, extending the blooming period and nectar availability. Bumblebees are the primary pollinators, using their weight to trigger the flower’s pollen-releasing mechanism.

The deep taproot system makes wild lupine incredibly drought-tolerant once established, though young plants need consistent moisture their first year. This root system also fixes nitrogen from the air, actually improving soil fertility for neighboring plants. Wild lupine thrives in the sandy, acidic soils that challenge many other perennials, making it perfect for difficult garden spots.

Beyond supporting Karner blue butterflies, wild lupine attracts various native bees and other beneficial insects throughout its May to July blooming period. The compound leaves create attractive foliage texture even when plants aren’t flowering. Seed pods develop after flowering, providing food for birds and opportunities for gardeners to collect seeds for propagation.

Plant wild lupine in full sun in sandy, well-draining soil – it actually prefers poor soils over rich, amended garden beds. The plants can be challenging to establish from transplants due to their deep taproots, so direct seeding often works better. Scarify seeds by rubbing with sandpaper before planting to improve germination rates. Once established, wild lupine typically lives many years and may self-seed in suitable conditions.

9. Goldenrod (Solidago species)

Goldenrod gets unfairly blamed for hay fever, but this bright yellow native actually produces heavy, sticky pollen that doesn’t become airborne – ragweed is the real culprit blooming at the same time. Michigan’s various goldenrod species create spectacular fall displays while providing crucial late-season nectar for butterflies, bees, and other pollinators preparing for winter. Each flower head contains hundreds of tiny individual flowers packed with nectar and pollen.

Different goldenrod species bloom from late summer through October, creating succession plantings that extend pollinator support through fall. Monarch butterflies particularly depend on goldenrod nectar to fuel their southern migration, while native bees use the protein-rich pollen to provision winter nests. Over 100 different insect species rely on goldenrod for food or shelter.

Michigan gardeners can choose from several native goldenrod species depending on their site conditions and design goals. Showy goldenrod works well in formal gardens, while Canada goldenrod naturalizes beautifully in meadow settings. Most species spread through underground rhizomes, creating impressive colonies over time that provide concentrated pollinator resources.

Plant goldenrod in full sun to light shade in average garden soil – most species aren’t particular about soil conditions as long as drainage is adequate. The plants typically reach two to four feet tall depending on species and growing conditions. Cut back in late winter to make room for new growth, or leave seed heads standing to feed birds through winter months.

10. Wild Ginger (Asarum canadense)

Wild ginger plays a different role in pollinator gardens, supporting specialized ground-dwelling insects with its unusual burgundy flowers that bloom hidden beneath heart-shaped leaves. Flies and fungus gnats serve as primary pollinators, attracted by the flowers’ carrion-like scent – not pleasant to humans but irresistible to these beneficial insects. The flowers bloom at ground level in early spring when few other nectar sources are available.

The attractive heart-shaped leaves create excellent groundcover in shaded areas where grass struggles to grow. Wild ginger spreads slowly through underground rhizomes, forming dense colonies that suppress weeds naturally. The leaves remain attractive throughout the growing season, providing textural interest even when the inconspicuous flowers aren’t visible.

Michigan’s native wild ginger thrives in the same woodland conditions where trilliums and other spring wildflowers grow naturally. The plant prefers rich, moist soil with plenty of organic matter – conditions easily created by adding compost or leaf mold to planting areas. Once established, wild ginger requires minimal maintenance and actually benefits from being left undisturbed.

Plant wild ginger in partial to full shade in consistently moist, well-draining soil rich in organic matter. The plants work beautifully as groundcover under trees, along shaded pathways, or in woodland gardens. Space plants 12-18 inches apart for eventual coverage, though expansion happens slowly. The rhizomes have a ginger-like fragrance when crushed but aren’t related to culinary ginger and shouldn’t be consumed.

11. Buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis)

Buttonbush creates unique spherical flower heads that look like white pincushions studded with protruding stamens, attracting butterflies, bees, and hummingbirds with their abundant nectar. Each round flower cluster contains dozens of individual tubular flowers that bloom from June through September, providing extended pollinator support during peak summer months. The unusual flower structure makes buttonbush easy to identify and adds architectural interest to garden designs.

Native to Michigan’s wetland edges, buttonbush tolerates both flooding and drought conditions once established, making it valuable for rain gardens and areas with variable moisture. The shrub typically reaches four to six feet tall and wide, creating substantial habitat for both pollinators and birds. Waterfowl eat the seeds, while the dense branching provides nesting sites for various bird species.

Butterflies seem particularly drawn to buttonbush flowers, with swallowtails, skippers, and hairstreaks regularly visiting the nectar-rich blooms. Hummingbirds also appreciate the tubular flowers, though they must compete with bees and butterflies for access. The long blooming period makes buttonbush especially valuable when many other shrubs have finished flowering.

Plant buttonbush in full sun to partial shade in moist to wet soil conditions – it’s one of the few shrubs that actually prefers wet feet. The plant works well near ponds, in rain gardens, or in low-lying areas that stay moist. Pruning in late winter maintains shape and encourages vigorous flowering. The spherical seed heads provide winter interest and bird food if left standing through the dormant season.

12. Wild Geranium (Geranium maculatum)

Wild geranium carpets Michigan woodlands with delicate pink flowers each spring, providing early nectar when most garden plants are just emerging from winter dormancy. The five-petaled flowers feature intricate purple veining that guides pollinators to nectar sources, while the palmately divided leaves create attractive textural groundcover throughout the growing season. Small bees and syrphid flies are primary pollinators, though butterflies occasionally visit the flowers.

The fascinating seed dispersal mechanism makes wild geranium fun to observe in late spring when seed pods mature. The pods split explosively, flinging seeds several feet away from parent plants – children love watching this natural catapult system in action. This mechanism helps wild geranium establish new colonies gradually without becoming invasive or weedy.

Michigan gardeners appreciate wild geranium’s adaptability to various light conditions, from partial sun to fairly deep shade. The plants form slowly expanding clumps through short rhizomes, creating natural drifts over time. Wild geranium pairs beautifully with other spring wildflowers like trillium, bloodroot, and wild columbine in woodland garden settings.

Plant wild geranium in partial shade to shade in well-draining soil enriched with organic matter. The plants typically reach 12-18 inches tall and work well in woodland borders, naturalized areas, or as groundcover under trees. Wild geranium goes dormant in midsummer if conditions become too dry, but returns reliably each spring. Established plants require minimal care and actually prefer being left undisturbed.

13. Spicebush (Lindera benzoin)

Spicebush supports specialized relationships with spicebush swallowtail butterflies, serving as their exclusive caterpillar host plant while providing early spring nectar for various pollinators through small yellow flower clusters. The tiny flowers appear before leaves emerge, making them particularly valuable when few other nectar sources are available. Male and female flowers occur on separate plants, so both are needed for berry production.

The aromatic leaves and twigs release a spicy fragrance when crushed, explaining the common name and historical use as a seasoning substitute. Spicebush typically grows as an understory shrub in Michigan’s deciduous forests, reaching six to twelve feet tall depending on light conditions. The bright yellow fall color creates spectacular displays in woodland gardens.

Female spicebush plants produce bright red berries in fall that provide high-energy food for migrating birds, particularly thrushes and vireos. The berries are also edible for humans and were traditionally used by Native Americans for seasoning. However, berry production requires both male and female plants in proximity for pollination.

Plant spicebush in partial shade to shade in moist, well-draining soil rich in organic matter. The shrub adapts to various soil conditions but prefers consistent moisture, especially during establishment. Spicebush works beautifully in woodland gardens, naturalized areas, or as understory planting beneath larger trees. The plants are either male or female, so purchase several specimens to ensure berry production and support spicebush swallowtail populations.

14. Nodding Onion (Allium cernuum)

Nodding onion creates charming drooping flower clusters that seem to bow politely in summer breezes, their pink to white blooms attracting small bees, beneficial wasps, and syrphid flies throughout the summer months. Unlike many ornamental alliums, nodding onion is native to Michigan and perfectly adapted to our climate extremes. The gracefully arching flower stems create movement in garden designs while the mild onion fragrance helps deter deer and rabbits.

Each flower head contains dozens of small individual flowers that open over several weeks, extending the blooming period from July through September. Native bees particularly appreciate the abundant pollen and easily accessible nectar, while the flowers also attract beneficial predatory insects that help control garden pests. The grass-like foliage blends naturally with other perennials and native grasses.

Nodding onion thrives in the well-draining soils and full sun conditions that challenge many other perennials, making it perfect for rock gardens, prairie plantings, or difficult slopes. The bulbs multiply gradually over time, creating naturalized colonies that require no maintenance once established. The dried seed heads provide winter interest and food for seed-eating birds.

Plant nodding onion bulbs in fall in full sun to light shade in well-draining soil – they actually prefer lean conditions over rich, amended soils. The plants reach 12-18 inches tall and work well in front to middle border positions. Allow foliage to die back naturally to nourish the bulbs for next year’s growth. Nodding onion self-seeds readily in favorable conditions but isn’t aggressive or weedy.

15. Serviceberry (Amelanchier species)

Serviceberry transforms Michigan landscapes twice each year – first with clouds of white spring flowers that feed early pollinators, then with sweet purple berries that humans and wildlife both treasure. The delicate five-petaled flowers appear just as native bees emerge from winter dormancy, providing crucial early-season nectar when few other sources are available. Various native bee species, including mason bees and mining bees, depend on serviceberry for spring sustenance.

Michigan gardeners can choose from several native serviceberry species ranging from small shrubs to medium-sized trees, all providing similar pollinator value with different landscape applications. The flowers appear before or with emerging leaves, creating spectacular displays against bare spring landscapes. Serviceberry also offers multi-season interest with attractive summer foliage, fall color, and interesting winter bark texture.

The resulting berries ripen in midsummer, providing food for over 40 bird species including robins, cardinals, and cedar waxwings. Humans can also harvest the sweet, almond-flavored berries for pies, jams, or fresh eating – though you’ll need to compete with the birds for the best fruits. The berries are rich in antioxidants and were traditionally important food sources for Native Americans.

Plant serviceberry in full sun to partial shade in well-draining soil with consistent moisture, especially during establishment. Most species adapt to various soil conditions once established. Serviceberry works beautifully as specimen plants, in naturalized areas, or as part of mixed shrub borders. Minimal pruning is needed beyond removing dead or damaged branches in late winter.